by Kathryn Hadley,

A press reception was organised this morning at the House of Lords to mark the completion of a project begun in January 2008 to recreate six paintings of the Armada tapestries, which were destroyed in the fire at the Palace of Westminster almost 200 years ago. The tapestries were originally commissioned to record one of the greatest episodes of British history; but the story of the tapestries themselves is equally great, and fascinating.

It begins 418 years ago, in 1592, when Lord Howard of Effingham, who had served as Lord High Admiral at the time of the Spanish Armada, commissioned the Dutch naval artist and first seascape painter, Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1566-1640) to create a series of ten tapestries to commemorate the British victory. The tapestries were woven in Brussels by Francis Spieringx. They cost £1,582, the equivalent of 87 years wages for a workman in 1590. They are believed to have measured 14 feet in height and between 17 and 28 feet in width and were interwoven with gold and silver thread. When they were completed, in 1595, they initially hung in Lord Howard’s Chelsea manor. They were then moved, in 1616, to his new London residence, Arundel House, before being sold to King James I for £1,628.

In the early 1650s, the tapestries were transferred to the Royal Palace of Westminster, where they hung in the then House of Lords Chamber, known as the Parliament Chamber. In 1801, when the Peers moved to the Court of Requests, a larger chamber which suited the need for increased seating after the Act of Union with Ireland, the tapestries followed suit. They hung in the Court of Requests until the fire on October 16th, 1834, in which all ten tapestries perished.

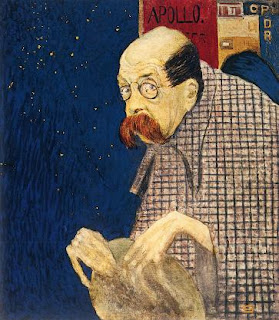

The significance and influence of the tapestries had been considerable. They were me ntioned in debate on several occasions and were used as propaganda. In 1798, for example, when concern over a possible French invasion was being debated, they were used to arouse patriotic popular support against the French forces. The artist James Gillray was commissioned to produce images that ‘might rouse all the People to an active Union against that invasion’. In a series of satirical prints entitled Consequences of a successful French Invasion, he depicted a French Admiral ordering his men to destroy the tapestries in the Lords Debating Chamber.

ntioned in debate on several occasions and were used as propaganda. In 1798, for example, when concern over a possible French invasion was being debated, they were used to arouse patriotic popular support against the French forces. The artist James Gillray was commissioned to produce images that ‘might rouse all the People to an active Union against that invasion’. In a series of satirical prints entitled Consequences of a successful French Invasion, he depicted a French Admiral ordering his men to destroy the tapestries in the Lords Debating Chamber.

House of Lords Researcher, Julian Dee, whose research formed the basis of the proposal for the recreation of the tapestries, underlined the changing historical significance of the tapestries:

Seven years after the fire, in 1841, during the construction of the New Palace of Westminster, a Fine Arts Commission chaired by Prince Albert was established in order to oversee the production of artwork for the interior of the palace. It was decided that the Prince’s Chamber would be illustrated with subjects from Tudor history and a space was designed to hang six paintings of the original Armada tapestries. The paintings were to be based on a series of engravings of the tapestries created in the 1730s by the artist John Pine. Pine’s engravings were the only surviving record of the tapestries.

However, when Prince Albert died, in 1861, only one of the paintings had been completed. It was not until 1907, that it was proposed, once again, to recreate the Armada tapestries. But once again, the Armada Tapestry proposal failed to be realised. One hundred years later, in 2007, it was proposed, for the third time, that a generous donation by Mark Pigott OBE should be used to recreate in painted format the 16th-century Armada tapestries. Anthony Oakshett, the lead artist on the project, began his work to recreate the tapestries the following year, using Pine’s 18th-century engravings and the only completed painting in the series The English Fleet pursuing the Spanish Fleet against Fowey as his key historical sources.

However, when Prince Albert died, in 1861, only one of the paintings had been completed. It was not until 1907, that it was proposed, once again, to recreate the Armada tapestries. But once again, the Armada Tapestry proposal failed to be realised. One hundred years later, in 2007, it was proposed, for the third time, that a generous donation by Mark Pigott OBE should be used to recreate in painted format the 16th-century Armada tapestries. Anthony Oakshett, the lead artist on the project, began his work to recreate the tapestries the following year, using Pine’s 18th-century engravings and the only completed painting in the series The English Fleet pursuing the Spanish Fleet against Fowey as his key historical sources.

The result is spectacular. On Monday, June 21st, members of the public will be able to see the paintings on a tour of parliament for the first time. In the autumn, they will be permanently moved to the Prince’s Chamber where they were originally designed to be hung. Try to spot Anthony Oakshett’s depiction of Mark Pigott as a 16th-century nobleman on horseback in the right-hand corner of the last painting in the series!

It begins 418 years ago, in 1592, when Lord Howard of Effingham, who had served as Lord High Admiral at the time of the Spanish Armada, commissioned the Dutch naval artist and first seascape painter, Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1566-1640) to create a series of ten tapestries to commemorate the British victory. The tapestries were woven in Brussels by Francis Spieringx. They cost £1,582, the equivalent of 87 years wages for a workman in 1590. They are believed to have measured 14 feet in height and between 17 and 28 feet in width and were interwoven with gold and silver thread. When they were completed, in 1595, they initially hung in Lord Howard’s Chelsea manor. They were then moved, in 1616, to his new London residence, Arundel House, before being sold to King James I for £1,628.

In the early 1650s, the tapestries were transferred to the Royal Palace of Westminster, where they hung in the then House of Lords Chamber, known as the Parliament Chamber. In 1801, when the Peers moved to the Court of Requests, a larger chamber which suited the need for increased seating after the Act of Union with Ireland, the tapestries followed suit. They hung in the Court of Requests until the fire on October 16th, 1834, in which all ten tapestries perished.

The significance and influence of the tapestries had been considerable. They were me

ntioned in debate on several occasions and were used as propaganda. In 1798, for example, when concern over a possible French invasion was being debated, they were used to arouse patriotic popular support against the French forces. The artist James Gillray was commissioned to produce images that ‘might rouse all the People to an active Union against that invasion’. In a series of satirical prints entitled Consequences of a successful French Invasion, he depicted a French Admiral ordering his men to destroy the tapestries in the Lords Debating Chamber.

ntioned in debate on several occasions and were used as propaganda. In 1798, for example, when concern over a possible French invasion was being debated, they were used to arouse patriotic popular support against the French forces. The artist James Gillray was commissioned to produce images that ‘might rouse all the People to an active Union against that invasion’. In a series of satirical prints entitled Consequences of a successful French Invasion, he depicted a French Admiral ordering his men to destroy the tapestries in the Lords Debating Chamber.House of Lords Researcher, Julian Dee, whose research formed the basis of the proposal for the recreation of the tapestries, underlined the changing historical significance of the tapestries:

‘These recreated images will tell us something about every generation that has

risen since Elizabethan times. James I displayed them in the Banqueting

Hall to receive the Spanish Ambassador. It has been suggested that in so doing

perhaps he could pursue dialogue with Spain without the appearance of

weakness. By contrast, his son Charles I folded these martial images away

for much of his reign. Cromwell's men had "The Story of '88" displayed in

Parliament so that generations of peers - most notably the Earl of Chatham -

would evoke the memory of the heroes commemorated in the tapestry

borders. When it was said that Napoleon wanted to put the Bayeux Tapestries

on a pre-invasion tour of France, it was suggested the same be done in Britain

for the Armada ones.’

Seven years after the fire, in 1841, during the construction of the New Palace of Westminster, a Fine Arts Commission chaired by Prince Albert was established in order to oversee the production of artwork for the interior of the palace. It was decided that the Prince’s Chamber would be illustrated with subjects from Tudor history and a space was designed to hang six paintings of the original Armada tapestries. The paintings were to be based on a series of engravings of the tapestries created in the 1730s by the artist John Pine. Pine’s engravings were the only surviving record of the tapestries.

However, when Prince Albert died, in 1861, only one of the paintings had been completed. It was not until 1907, that it was proposed, once again, to recreate the Armada tapestries. But once again, the Armada Tapestry proposal failed to be realised. One hundred years later, in 2007, it was proposed, for the third time, that a generous donation by Mark Pigott OBE should be used to recreate in painted format the 16th-century Armada tapestries. Anthony Oakshett, the lead artist on the project, began his work to recreate the tapestries the following year, using Pine’s 18th-century engravings and the only completed painting in the series The English Fleet pursuing the Spanish Fleet against Fowey as his key historical sources.

However, when Prince Albert died, in 1861, only one of the paintings had been completed. It was not until 1907, that it was proposed, once again, to recreate the Armada tapestries. But once again, the Armada Tapestry proposal failed to be realised. One hundred years later, in 2007, it was proposed, for the third time, that a generous donation by Mark Pigott OBE should be used to recreate in painted format the 16th-century Armada tapestries. Anthony Oakshett, the lead artist on the project, began his work to recreate the tapestries the following year, using Pine’s 18th-century engravings and the only completed painting in the series The English Fleet pursuing the Spanish Fleet against Fowey as his key historical sources.The result is spectacular. On Monday, June 21st, members of the public will be able to see the paintings on a tour of parliament for the first time. In the autumn, they will be permanently moved to the Prince’s Chamber where they were originally designed to be hung. Try to spot Anthony Oakshett’s depiction of Mark Pigott as a 16th-century nobleman on horseback in the right-hand corner of the last painting in the series!

Images (Palace of Westminster Collection):

- Richard Burchett, The English fleet pursuing the Spanish fleet against Fowey

- James Gillray, Consequences of a successful French Invasion

- Anthony Oakshett, Drake takes De Valdes's galleon; the Lord Admiral pursues the enemy

.JPG)

.JPG)